Coming to Kenya has allowed us to learn about the horrific abuse of land, people and power that formed Britain’s colonial crimes. I understand this topic is still relevant and sensitive for many Kenyan families, and whilst I write here with objective distance, I’m not blind to the suffering of Kenyans at the hands of my countrymen. Some of these victims are still alive today.

Our impending return to Britain reminds us that we’re British, and the Queen’s jubilee and London Olympic games are all stirring our sense of nationhood. But never before have we been personally confronted with the idea of Britain as war criminal; it’s a thought that has lingered all year and only now finds its way into the blog.

The opening line of The Go Between reminds us that ‘The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.’ The colonial Britain I write about here feels foreign in every way. That Britain is not my Britain, I think. But here in Kenya, not everyone makes that distinction….

A little background…

Dan and I are British.

Born in the 1980s, into families born and bred in Europe, we have no

personal links to the 80,000 Britons who gradually settled in Kenya starting in

the 1890s. But, many of the Kenyans we

meet today seem to align us directly with these long-dead white settlers.

Arriving in dribs and drabs, the first few British

people in Kenya initially worked alongside the local population to farm tea and

coffee. So far, so peaceful. But Britain got serious about colonising

Kenya in the 1920s. Encouraging more and

more settlers to join this corner of East Africa and help turn a profit, the

British government soon figured out that to sustain all the white people and

all the crops, they would need to gain control of even more land. Enforcing land ownership laws, the

colonialists worked hard to move the local population or demand taxes for

‘squatting’ on their land (hey, it worked in Ireland!)

The backlash against this treatment became known as the Mau Mau rebellion; rebels who hid in the forests and during the 1950s used violent means to… ‘encourage’ the British to go home. Whilst the rebellion failed to force the immediate withdrawal of British settlers, the violence and need for increased security convinced the British government to join the wind of change blowing through Africa, and grant Kenya independence in 1963.

|

| Jomo Kenyatta and Dedan Kimathi: Kenyan heroes |

|

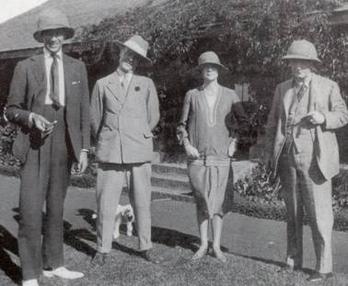

| Mama and Papa Trenchard, in the Mau Mau caves |

When my Mum and Dad visited Kenya in March, and we

took a guided walk through the foothills of Mount Kenya to visit some ‘Mau Mau

caves’ where the rebels hid and trained.

Our guides were chatty young Kikuyu guys talking proudly about the Mau

Mau freedom fighters who, in their eyes, fought for Kenya’s freedom and won. My parents, who grew up in 1950s Britain,

remember that the UK press (naturally) spun it very differently. The newspaper headlines of their childhoods

told of evil black Mau Mau terrorists, waiting in the shadows to butcher your

family.

It seems that the relationship between Kenya and

Britain is long, complex, interwoven and with very dark chapters. This post is about how I see Kenya’s colonial

history impacting on its present, and what it’s like to be British and live in

today’s Kenya.

‘Our colonial

masters gave us so much’

The caretaker at work is over 70. He loves to grasp me by the hand and sing the

praises of the British people. The quote

above is his. ‘Everything great comes

from Britain’, he tells me, ‘I love Queen Elizabeth.’ Another time, ‘If you want something that is

good quality, look for the Made in

England stamp on it. All the very

best things are made in England, they last a lifetime. Now in Kenya we are just given poor quality

goods from China, it’s an insult.’

I try and explain that whilst Britain was still

producing many such goods in the 1950s, mass production in England has ceased. I tell him that in modern Britain most of our

goods are also made in China, and only last a short time. I assure him that it’s not a punishment for

Africans.

This gentleman has strong views that the British way

is the best way, but as he explains his love for strict rules, correct dress

sense and a monarchy beloved by all, I start to realise the Britain he loves is

long gone. I see the culture he admires as

a relic of Britain’s past, left behind by the Brits that pulled out in

1963. I wonder how to tell him that

Britain has moved on.

But it’s not just our caretaker. Kenya clearly retains some parts of British

culture frozen forever from the 50s and early 60s. Whilst the influence of local culture

sometimes aligns with these 20th century leftovers, there are

several examples which lead me to think that British culture I’ve only ever

associated with my grandparents, is alive and well in today’s Kenya:

·

Formality is everywhere. Greetings and handshakes are very important, every meeting must have

a chair and a secretary, prayers are offered before and after meetings and for

all meals. Speakers will offer welcome

and thanks to all VIPs in attendance, and the phrase ‘All protocols observed’

will follow before speech commences proper.

Far from an open-plan office, my colleagues are enclosed in small

offices, behind doors that need knocking before opening. They laugh at my

insistence of ‘an open-door policy’ and are puzzled that I don’t want

privacy.

·

Hierarchy and gender roles are strictly observed here, and not just because traditional tribal beliefs are held today. It feels to me as if the social rules have

been enforced by British meddling. In

the Kenyan organisation I work in, deference to your seniors is paramount and

upward feedback never given. Important

issues must only be raised by a peer (never an inferior) and trickier

conversations often never happen, and if these sticky points are raised, they

are raised by the men. Whilst having a

‘gender balance’ is paid lip-service on a panel or in a delegation, women

criticising men is unheard of, and serving tea is always left to my female

colleagues. When Dan folds up the dry

washing from the clothes line outside, the housegirls all stand and watch in

curiosity. I’m fairly sure all these

women disapprove of me, ‘she leaves her husband

to bring in the washing!’

|

| Ateeeeeen-shun! |

·

Boy Scouts are old school. The Scouting movement was founded in 1907 by Kenyan resident and

British citizen Lord Robert Baden-Powell (he’s actually buried here, in Central Kenya). Dan

and I attended an event where the highlight was the scouts: Kenyan children

(girls and boys) in long socks and neat caps marching one-two onto their ‘parade

ground’ to the shouts of a Sergeant Major who was not older than 16. They then drilled in unison, and stood to

attention for ‘inspection’ by the event’s VIP.

When did British scouts stop marching?

·

Church is central. There are many reasons why the majority of

Kenyans are committed Christians, but being a former colony must surely be top

of the list. White settlers not only

brought the good news, but also clear rules on how to worship: every Kenyan I

know attends church on Sunday morning, some are preachers and tee-totallers for

religious reasons. Others tell me with a

straight face about the people they know who have been bewitched by evil

spirits. I am reminded that weekly

church attendance and an assumption that EVERYONE attends is an aspect of 1950s

Britain that exists no more.

|

| Busy pavements of South B: it's Church O'clock |

·

Kenya’s currency is the shilling; and

shorthand is ‘bob’. The only person I

know in the UK who still refers to money as bob is my Grandad, and he was born

in 1917.

·

Even clothing reminds me of Britain in an earlier age. Kenyans are SMART: suits are

worn everywhere, shoes are buffed by the shoe-shiners on every street corner

and washing clothes is almost the nation’s pastime. My male colleagues all wear vests under their

shirts, and keep a cloth handkerchief handy.

Sunday best is not an anachronism here: dresses are pressed, children

are scrubbed up and our female Kenyan friend is criticized for wearing trousers

to church. In 2012.

·

Views are conservative. Along with taking ‘woman’s place’ quite

seriously, Kenyans join the rest of Africa in not accepting or even

comprehending homosexuality. I've already written here about how views on marriage

are more conservative than in modern Britiain, but along with that I’d place

the views of your community, parents and your own sense of duty all having a

big say in your life choices here.

Whilst this world-view is not unique to Britain in the last century, I

offer an opinion that it has at least been shaped

by Britain’s 70-year involvement in Kenya.

I’m making a well-trodden argument that culture imported from elsewhere tends to remain ‘pure’ (frozen in time), whilst the motherland that spawned that culture continues to evolve and even change quite radically. It’s been suggested that the second and third generation white settlers who still live in Kenya maintain the more conservative tenets of the Britain their families left many years ago. I’m told that Indian families who’ve been in Kenya for several generations are much stricter in their faith and views than their relatives who continue to live to Rajasthan and Gujarat. These modern Indians are also struck by the same déjà vu as me, when visiting. They too experience this phenomenon of frozen culture.

I know these old-world behaviours don’t account for every Kenyan, but I see the UK being admired by many areas of society. Good friends of ours are young, professional, urban, liberal Kenyans. They love the UK – ‘I really want to visit, it really seems like a place I would like’. They tell me about their favourite Dizzy Rascal track and they LIVE for the English Premier league.

‘You people used to shoot Africans like birds’

I think it’s important to mention that not all aspects of this frozen culture show themselves as attempts to copy the colonialist thought, word and deed. We’ve discovered that hatred for the British has also not died out in every quarter, although we hear more praise than anger, mainly because (in another homage to Britain?) Kenyans are generally unfailingly polite.

An exception is the landlord for our apartment building, who on finding out where we were from, unleashed several comments at Dan that suggested we should personally atone for the sins of our fathers. The quote above is his. ‘I used to hate people like you’ he spat at Dan. How are we supposed to feel about that?

Whilst we may not hear of it, it’s obvious the anger still exists. The Chairman of the Nairobi branch of my organization is Kikuyu, from Central Kenya. I was attending a meeting of his members; he had to explain ahead of time to some Kikuyu gentlemen in his group that a Briton would be in their midst. ‘They weren’t happy, ‘ he tells me, ‘But I explained you are OK, that you are helping us’. It’s a totally strange feeling, that for the first time in my life, I personally, would be smeared with the crimes of the British empire.

The New Colonialists

An American friend asks us, ‘How do you feel, living in Kenya, when your people committed so many crimes against Kenyan people?’ A tricky question to answer. I suppose that much like today’s white Americans feeling outrage for the millions of Africans captured and shipped to US shores in the 19th century, I did not personally participate in subjugation of the Kenyan people, so any feelings of guilt or responsibility are diluted by distance, my own horror at colonial crimes and the feeling that it’s just all ancient history.

We know now there are living Kenyans who hate us - white people will always be the enemy they spent their early lives fighting against. But this is a small majority. Our Kenyan friend is aghast at how her ancestors let foreigners take over their land and abuse their people. ‘We Kenyans were so stupid! We brought it on ourselves.’ But she also reminds us that it’s all in the past, that most Kenyans don’t see Kenya as a former colony from one Jamhuri (Independence) Day to the next.

While Britain’s past might linger in Kenya’s present, in clothes and attitudes and marching scouts, the days of colonisation is over, and as 50 years of independence becomes 100, no living person will have experienced the abuses Britain brought on Kenya. These days the foreigners who arrive to live in Kenya are, overwhelmingly, NGO workers like ourselves. Are we the new settlers? I can already see the impact we are having on the language of development, of how poverty is spoken about and tackled, how (white) donors expect Kenyan charities to behave more and more like the London office. Is our way the right way? While we have greater economic might, we will always be able to exert influence, but it can never be as damaging as the first time we came. That is now history.

No comments:

Post a Comment